The wait on my shoulders & The pork in my pie.

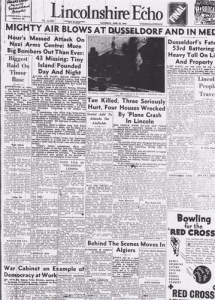

As part of The Grandstand Project, I was involved in the construction and execution of two pieces, ‘The Waiting Room’ and ‘EXPO ’69’. The reason for this is solely a result of research and the vast amount of history that the site had to offer. The idea for the ‘EXPO ‘69’ piece first formed when researching on a visit to the Lincolnshire Archives, the three of us who eventually collaborated on this piece were drawn to the articles and advertisements about the event which had happened forty four years before. The pictures which we took that day eventually formed the window coverings for the space and remained with us throughout the process as a form of inspiration, insuring we all worked towards the same vision, one of nostalgia and fun, juxtaposing the dreariness of the site and darkness of other pieces.

In contrast to ‘EXPO ‘69’, ‘The Waiting Room’ was inspired entirely by the space. The four of us chose the room and then went away and did research. Upon bringing the research together, one commonality ran through all aspects of that room’s history, people waited there. With the idea of waiting we set out chairs as a basis to work from and took to researching behaviour and control as well as more thoroughly into the individual stories of the people who waited and why.

At 14:00hrs on the 8th of May 2015 I opened the doors to the Grandstand and announced the performances beginning to the four audience members who were stood in the rain waiting to enter the space. The first piece they saw was ‘EXPO ‘69’ as this was positioned in the entrance hall. The piece consisted of a small 7ft by 9ft room with two windowed walls, two brick walls and a sloped Perspex roof. We covered the roof in red material which hung like a tent roof, had a table of food which reflected the menus found during research, covered windows in collages of relevant pictures and newspaper cuttings, hung bunting and a banner on the railings outside, installed shimmer curtains on each doorway to enclose the space, had coloured lights which reflected on every surface, made a dress out of foil to represent the metal dress showcased on the runway of the EXPO, had Mr and Mrs EXPO sashes to represent the competition of the time and finally played the music of a performer from the original EXPO. All this created a space full of the atmosphere and nostalgia which captured history in a fun and unexpected way.

‘The Waiting Room’ was set in a space down a corridor and away from the main action of the day. On the day only four performances of fifteen minutes took place with a fifteen minute interval between the end of one and beginning of the next in order to re-set the space. The space contained eleven chairs and a receptionist desk, there was a clock on each chair and others positioned around the room. Also on the chairs were envelopes containing text to be read out or instructions to be followed at certain times. The envelopes were designed in such a way that a chain of events would happen as we wanted it to and that the performance would end with a reading by the receptionist of a list she had typed during the piece, before me reciting the poem ‘Funeral Blues’ by W. H. Auden to which all participants removed the batteries from their clocks, placed them in a jar and left. The piece was about the pressures of waiting and the effects of time, as well as stepping outside the boundaries and constraints which these put on us.

Waiting for an epiphany & The singing, swinging sixties.

Week one saw us being introduced to the space and then exploring it for ourselves. We measured the space with our eyes and bodies, as well as gathering objects from around the site and bringing them together in the largest of the spaces. Once we had explained why we had chosen our objects, we began a discussion of our first impressions of the site, with words of description including dull, old, painted, clinical and characterless to name a few. Finally we chose a room to explore in more detail. It is strange that the room in which I spent the first hours of my time at the site was the room in which the majority of my work took place. The room I chose, along with three others, was then dubbed the ‘RAF room’ for the mural above the fireplace.

The mural, as the most prominent feature of the room, was the thing which grabbed our attention and which we instantly started to research on our phones. We found out almost instantly that the Grandstand had been used to test WWII planes before dispatching them overseas. Once we had this information, however, the next issue was knowing what to do with it and completely by chance I happened to roll over and notice that, from the angle that I was laid, the lights on the ceiling looked just like those either side of a runway. For the piece that we showed that week, we played airplane noises from our phones and asked audience members to lie in the place that I had, whilst we explained some of the history we had surfaced.

Although this was a simple piece it established a way forward which saw research and spaces come together to create something entirely new and different. Week two, however, could not have portrayed a more different message. ‘Drifting through Spaces’ was the allocated reading and this paved the way for a completely more organic exploration of a space. Smith says that you should ‘Avoid art’ and ‘seek those public places that are ‘hidden in plain sight’ and not visited by many’ (Smith, 2010 p.118). I was not in attendance for this session, however the reading still had the effect of making me stop and question whether history has to be such an important factor in a site specific piece, or is it simply about the space and what you find and what can be done with it. For example, if we were applying this technique in week one, all research would be discounted and all that would matter is the space, a difficult task in a site which oozes history like the Grandstand does.

The third week of the project was a huge turning point for our process and whilst visiting the Lincolnshire Archives we split into smaller groups of interest and ideas for pieces began to form. The two things that interested me were, as I mentioned, the advertisements and newspaper articles for the EXPO ’69 and the pre-world war two plans for the Grandstand which involved a mortuary, a viewing room and a waiting room, the room in which I had been mainly working.

With the new information fresh in our heads, we worked that week on extending two ideas which had been established in the previous session, one group inside and one group outside. I worked inside on a piece which dealt with the mortuary idea and played with a scene of scattered chairs and shoes in which we fell whilst walking through the space in order to represent a battlefield. We then got up, found our shoes and then went to lay down in the ‘viewing room’ with a sheet over us to depict the transition from war to the Grandstand.

After this session I revisited Mike Pearson’s questions in ‘Site Specific Performance’ and answered a selection which would best explain my feelings about where we were in the process.

‘Am I purposefully lost in space, trying to get my bearings?’

Yes would have definitively been the answer before the session in week three. Now I only answer yes with some hesitancy, as I feel as if the space is starting to reveal itself to us, revealing its history, charm, struggle, loneliness, helplessness, willing and needs. As each one of these rounds the bend and canters into sight, it feels as if we are that much closer to understanding how we can draw attention to the things that the site speaks of, for it does speak, to each of us individually, instructing our decisions on performance whether consciously or not.

‘As I move around do I leave marks: ‘to walk is to leave footprints’ (Roms, quoted in Whitehead, 2006, p. 4)’

We are leaving ‘footprints’ and impressions on the site and the people who inhabit it alongside us. From something as little as a mother from the playgroup placing her hand on a pillar directly where a post-it note had resided the day before and wondering why it is sticky, to the memory the man walking his terriers will have of half of the group clambering along the railings of the courtyard area, to the litter which we may leave in the bins on a weekly basis and to a stray balloon making its way onto the sixth putting green, we leave marks, there is no doubt. (I have since thought about this and a piece of string from week 7 was still tied to a pillar in the waiting room when we left after our final performance). The final footprint we will leave will, inevitably be the performance, and as I grow more and more attached to the site, I feel that it is our duty, and my right to make known to others what the site has to offer today, and what it has offered in the past.

‘What are the circumstances of my presence? Am I a stranger or an inhabitant? Do I pass unnoticed or do I stick out? Are my actions clandestine or do I draw attention to myself?’

The answers to all of these questions will change the longer I spend time at the site, however, I feel that after reading Govan’s ‘Inhabited Spaces’ and ‘Architectural Spaces and the Haptic’, it wouldn’t be wise to forget that spectators will be asking themselves these questions and, at that time, will be reaching near opposite conclusions to us. Yi-Fu Tuan said that, ‘architectural space reveals and instructs’, with the suggestion that a cathedral (the building and parts thereof) becomes a symbol for the values it projects (Govan, 2007 p.114). In this light, whether the grandstand projects to us a feeling of loss, dilapidation, renovation, rejuvenation, hope, sorrow, misery, heartache, former glory or boredom, it is not a given fact that a spectator will see the same, meaning a performance with a high level of ambiguity is surely out of the question? The Grotowski example, which is provided in ‘Inhabited Spaces’, created a living environment in which spectators joined in, is this the way to draw an audience to the point of realising the subject and motive? The Reckless Sleepers example used the incongruity of an industrial backing and lavish tables dressed in period banquet style to heighten the irony of the space, is this a possibility to provide a clear subject and motive? Or, do we look at this another way, do we want to be so ambiguous that the audience can draw their own conclusions? Is it an idea to ask in some way what exactly they got from the performance? Do we want our audience to feel every single emotion of alienation and the feeling they’re intruding or that they simply don’t belong?.

‘Who am I and what am I doing?’

The answer which I gave at the time was ‘[Answer to follow shortly]’, and indeed it did.

(Pearson, 2010 pp.19)

From this point of the process it was a case of working from an initial short performance devised over one session and expanding and improving it into a piece which we were proud of and which fit the criteria. The Waiting room was a piece which developed subtly and slowly throughout the rehearsal stages. We thought of new ideas and took inspiration from existing works, tried them out on our peers and then moved on. One example of this was the idea taken from German artist S. Astrid Bin and their piece, One Thousand Means of Escape, involving paper airplanes being suspended in flight, all pointing in the same direction, providing the sense of a need to escape. This would have worked within our piece as a gradual installation which built over the four performances, however in practice, audience members weren’t that good in making paper airplanes and we weren’t any good at making them look good either.

http://www.astridbin.com/one-thousand-means-of-escape/

There were many setbacks similar to this, such as the idea of tagging our audience with a brown label as they came in, giving them a name and a reason to wait. We found that this overcomplicated things and discarded of the idea which we had originally seen as being a main part of the specificity of the performance to the site. After hours of worrying that our piece was not specific enough, we decided to go home and simply research whatever we could that had any relevance to the site. When we came back together we discovered that there were more than a few cases of people waiting in our space and we decided to write down their stories and experiment with the idea of reading them out during the performance. Eventually the audience read these out as part of the instructions in their envelopes in a style which had ties to Fuel Theatre’s ‘While you wait’ project which is a chance to listen to ‘a series of podcasts, each of which is a different meditation on the idea of waiting’. Ours was similar in that the stories which were read were also different ways of waiting; the difference being that the audience themselves performed our text. Along with this, many other ideas lasted the process, like the individual clocks on seats, the list of things which the receptionist typed during performance and read at the end, as well as the controlling of the audience through instructions in envelopes.

In the final days of the process three major things changed, our audience size shrunk to 8 from 21, our performance length went from 40mins to 15mins and we decided that a poem should read a poem at the end which linked well with the piece and its message. The poem was ‘funeral blues’ by W. H. Auden and the first line is ‘Stop all the clocks’, at this point I took the battery out of my clock as the receptionist began to pass round a jar for the audience to do the same. The batteries worked as a small scale gradual installation on the fireplace, but the poem had many further links to the site as it spoke about death, airplanes and clocks.

EXPO’s process was fairly simple; we knew from the outset that what we wanted was a small space with lights and music and food, fun and atmosphere. In the early stages, we planned a lot, there was no rehearsal as the installation piece would be unattended for the majority of the performance. One thing that did change during our process was the space, a decision which came because we found the original space too small for an audience to enjoy. When looking for a new space, we found that if we were to set the piece in the entrance hall, you could see the original Expo site, making our piece even more specific. Along with all the old ideas, such as taking menus from the archives and planning the food, making the foil dress and Mr & Mrs EXPO sashes, buying material to drape from the roof an over the table and plants to add to the ambiance, the new setting brought new elements to the piece, such as a text which echoed a task from week one of the process where we wrote letters to the Grandstand, the text was a combination of individual letters which my collaborators and I wrote from the Grandstand, here is an extract:

‘Throughout those years of ache and sorrow, one week in particular has etched its way into my mind in the form of the darkest memory, and never have I been as lonely as I was in the week of the 24th May 1969 … And now, (would you believe it?) all these years later, I am to host my own sample of EXPO69. So here is my plea to you, audience member; Imagine you are there, imagine the atmosphere, the excitement and the possibilities, smell the smells, hear the sounds and see the sights. Let me watch, like I always have, and see, for the first time in years, happiness, affection and appreciation.’

Once the setting changed things started to fall into place and a plan which was drawn up in the middle of the process was practically unchanged right up to the performance.

|

|

I’ve finished waiting & I’m all full up.

The performances are finished and I believe that we achieved reasonable success. For a site that is as remote as the Grandstand and a day as miserable as the 8th was, audience numbers were high enough that ‘The Waiting Room’ could run four successful pieces and ‘EXPO ‘69’ ran out of food. When I returned home my housemates who had been audience members described ‘The Waiting Room’ as ‘alienating’ and ‘like a real waiting room’, comments which I believe make the performance a success. From the lack of leftovers, the greasy fingerprints on the laminated texts and the number of audience who were dancing along to the music, I also feel that ‘EXPO ‘69’ served its purpose. In absolute honesty, better preparation for ‘EXPO ‘69’ is the only thing that could have improved the piece, along, of course, with a bigger budget. With ‘The Waiting Room’, I believe that we could not have improved it, only made it different, and as we changed so many aspects along the way, I feel like we reached the best possible performance in the end, the post-performance of burying a time capsule with something from each piece inside also added to this, signifying the constancy of the grandstand in an ever changing world as well as our faith that it will remain so for years to come.

My time in Site Specific has taught me many things, the diversity of performance, the influence of history and of a space and the importance of process, along with many others. Working at the Grandstand has had an unexpected effect on me, which is that I know feel more able to work in unconventional spaces, as well as feeling like when working in a traditional theatre, I can transfer the experiences and techniques I have learned in order to feel more comfortable with that space as well. I have learnt that any devising process draws on the values of site specific and that there are two different kinds of ‘place’, ‘On the one hand the kind of place in which Live Art practices are made, on the other, the kind of place in which Live art practices are presented’. ’ (Kiedan, 2006 p.8)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kiedan, Lois (2006) ‘This must be the place: Thoughts on Place, placelessness and Live art since the 1980’s’ in Leslie Hill and Helen Paris’ (ed.) Performance and Place, London: Plagrave Macmillan pp.8.

Smith, Phil (2010) Mythogeography: aguide to walking sideways, London: Triarchy Press, pp.118-121.

Govan, Emma (2007) Making a Performance. Coxon: Routledge P114-119.

Pearson, M. (2010) Site-Specific Performance. Palgrave Macmillan: London. P19.

Bin, Astrid: http://www.astridbin.com/one-thousand-means-of-escape/ [accessed 16th May 2014]

http://www.fueltheatre.com/projects/while-you-wait [accessed 16th May 2014]

![20140207_092405[1]](https://sitespecific2014mpi.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2014/02/20140207_0924051-e1392254373916-168x300.jpg)

![2014-03-06_00.53.22[1]](https://sitespecific2014mpi.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2014/03/2014-03-06_00.53.221-300x241.jpg)

![20140307_111710[1]](https://sitespecific2014mpi.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2014/03/20140307_1117101-300x168.jpg)

![20140508_102554[1]](https://sitespecific2014mpi.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2014/05/20140508_1025541-300x168.jpg)