Welcome to The Waiting Room.

The Waiting Room is the site-specific performance I have been part of developing for the past four months. The site was Lincoln grandstand and was performed on May 8th between two and five o’clock. There were four performances and each performance had a maximum capacity of eight audience members. The piece itself was fifteen minutes in length and depended highly on audience participation.

Inspiration for The Waiting Room came from various places, mainly the history of the site itself. A lot of research went into learning about the grandstand and we developed a performance that we felt responded to that history with influences for the structure of the performance being influenced by companies and practitioners such as Rotozaza and John Newling.

In terms of developing the piece, we had very early inspiration from Rotozaza which seemed to stick with us throughout but that influence was mainly in regards to the set up of the performance. Further developments and the content and structure of the piece really came from the research we carried out and the feedback we received throughout our process. Of course we did research into many practitioners who had created pieces surrounding the passing of time such as Tehching Hsieh’s Time Clock Piece (as is informally known). It was useful to do research into projects such as these because they gave suggestions for how we could emphasise the passing of time but as none of these elements really came into play in our site-specific performance therefore are not mentioned throughout this blog submission.

Other influences into our development are from the likes of Mike Pearson who’s works encouraged the exploration of the site and prompted me to ask questions about the site that I wouldn’t have thought of myself in regards to my rights being at the site: “Am I there by invitation or am I trespassing?” (2010, p.19) as well as encouraging me to allow my feelings toward the sit to inspire the creative process of developing a piece.

The start line.

My first visits to the grandstand were under the influence of Smith’s The Handbook To Drifting (extracts) particularly the third instruction, “get your nerves out…Walk slowly and look for meaning in everything.” (2010, p.119).

The main space I was introduced to was the grandstand community centre, a space that is used for a variety of things from children’s day care to a mosque once a week. The space that I was originally drawn to in the building was a small corridor lined with windows facing an enclosed outdoor area.

![Robinson, A. (2014) [Image online] Available from https://sitespecific2014mpi.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/2014/02/13/an-a-with-no-b/ [Accessed 12th May 2014].](https://sitespecific2014mpi.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2014/02/MG_7829-200x300.jpg)

Robinson, A. (2014) [Image online] Available from https://sitespecific2014mpi.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/2014/02/13/an-a-with-no-b/ [Accessed 12th May 2014].

Another space I found particularly interesting was what I fondly know as the RAF room. This is a slightly smaller room in the building which features a stunning RFC mural over the fireplace. Mike Pearson writes that when you are exploring a site you should ask yourself “How am I affected? What do I feel? What do I perceive? What do I experience?” (2010, p.22). I had a very strong personal response to this room because my Grandfather had served in the RAF for years, however I didn’t explore this space creatively first because I felt like the shape of the corridor was more exciting and had the potential to tell stories in an exciting way.

The archives and a breakthrough.

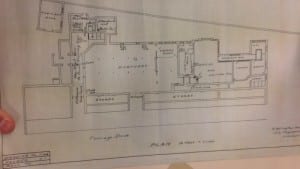

The next step in developing our pieces was to gain more knowledge of the history of the site and to do this I visited the Lincolnshire Archives. Here I was overwhelmed by the history of flight and Lincoln’s contribution to the services of the RFC and RAF during the world wars. More information found was a plan of the grandstand showing how it may have been used as a mortuary during WWII as if it happened the RAF room would have been used as an office/waiting room.

I also learned about an expo that took place on the West Common in 1969 and this caught my eye as well because I felt like everybody else was focusing on the more morbid elements of grandstand history; however I let the idea go because it didn’t actually happen in the site and I didn’t feel as much of a connection to the idea. I made the decision to create a piece that made reference to a lot of grandstand history because I felt as though none of it should be neglected. Alice suggested the original idea of The Waiting Room and we agreed that the content should acknowledge a great deal of grandstand past.

We proceeded to put The Waiting Room into practice and began with setting up the space as a waiting room. Twenty-one chairs were used and we also pulled round a table to create a ‘reception’ area. It was decided very quickly that we wanted to highly involve our audience and use influence heavily from Rotozaza, Etiquette. This is a piece in which two participants go into a café wearing head sets and follow the instructions given to them:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-iU7mzaktsQ

(RosieArches, 2010)

‘Etiquette exposes human communication at both its rawest and most delicate and explores the difficulty of turning our thoughts into words we can trust. A young girl and an old man lead the participants into several micro-situations, often borrowed from film or theatre, wherein the private worlds shared between two people split and reform incessantly.’ (Rotozaza, 2007).

This statement highlights two things: the term micro-situations to me implies a moment, such as the touch of a hand or the brushing of fingers, that to anybody who can’t feel it on their skin doesn’t even recognise it happen. Secondly, the manipulation that comes with the participants’ private world being connected and then split in a second. This is something I was instantly drawn to and this idea of controlling and manipulating participants was something that The Waiting Room set as its basis. Another piece that enforced this was Ligna, Radio Ballet which took place in the main train station in Hamberg, the following link is to a performance in 2003:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qI3pfa5QNZI

(Radiodispersion, 2008)

Ligna’s blog informs readers that:

‘A Radio Ballet is a radio play produced for the collective reception in certain public places. It gives the dispersed radio listeners the opportunity, to subvert the regulations of the space.’ (Ligna, 2008)

My first response to this piece was ignorant to its political groundings and I was merely attracted to a piece that made strange ordinary behaviour. The difference in pace and attitude of participants compared to the rest of the public, that contrast, is what I wanted for the waiting room.

Evidently both of these pieces involved using headsets to control the audience however we decided against this as we were limited to having only two channels on the headsets which would massively challenge the personal feeling we wanted participants to have. Instead we decided to use envelopes with instructions inside ion order to control our audience. This was meant to be reminiscent of letters sent during the war. The envelopes manage to keep the audience focused because they are constantly waiting for the right time and wondering what is in their envelope. We also discussed wearing name tags and giving them to audience members, a gesture towards the possible mortuary, we eventually decided that these could be fictional identities combined with actual people who perhaps worked or had a story to tell about the grandstand.

Waiting for time to pass us by.

The next step was to gain content for the performance; I decided to set up an online survey to ask the questions: what are you waiting for and what do you think the grandstand is waiting for? We eventually gained twenty-eight responses but we were unsure of exactly how to use them in the performance. What I found was strange was that very few of the things people said they were waiting for were durational and they certainly wouldn’t be spending their time in a room waiting for the events to happen: “This process of making strange enables the artist to relate to the site in a way that may educate, inspire and politicise an audience.” (Govan, 2007, p.122).

We moved on to the most important element of the performance, we had established that the piece should emphasise the passing of time in the grandstand and how we wished that we could stop time and preserve some of the things that had happened in the site because it all seemed to go completely unknown. We discussed the idea of a durational performance but quickly dismissed this as it would spoil the effects of timing all the instructions and envelopes to give to audience members. The agreed performance time was thirty minutes and we would emphasise the passing of time by giving each audience member a clock and having several clocks around the room, with a possible installation piece.

Instructing the audience.

The envelopes that we used contained instructions such as ‘go over to the kettle and turn it on, make yourself a coffee’ or ‘cry, audibly’.

![Milne, S. [image online] Available at https://sitespecific2014mpi.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/2014/03/10/talking-sense/](https://sitespecific2014mpi.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2014/03/image-1-300x225.jpeg)

Milne, S. [image online] Available at https://sitespecific2014mpi.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/2014/03/10/talking-sense/

Getting half way.

After another feedback session we started to work on the silence issue. We were inspired by John Cage’s 4’33 which highlights the fact that when you make no sound, what you can hear is music. We wanted to carry this idea of silence and the sound of clocks being the ‘music’ however we were encouraged to add narrative to fill silences. A specific narrative we were recommended was the poem Funeral Blues, W. H. Auden. This wasn’t included in our piece until we made a last minute decision about an installation at the end of the performance and the poem fit perfectly. We developed our other narratives using the public research we had done as well as what we knew people had waited for in the grandstand; a practitioner who influenced this was John Newling who carried out a site specific performance in a shopping centre in Nottingham. His Ecologies of Value, 2011 traded in what members of the public found valuable (just information) for a piece of a giant riddler jacket.

![Newling, J. (2013) 'Where a Place Becomes a Site: Values (part 1), 1995-2013' [image online] Available at http://www.john-newling.com/2013/05/where-a-place-becomes-a-site-values-part-1-1995-013/ [Accessed 10 May 2014].](https://sitespecific2014mpi.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2014/05/John-Newling-where-a-place-becomes-a-site-225x300.jpg)

Newling, J. (2013) ‘Where a Place Becomes a Site:Values (part 1), 1995-2013’ [image onlne] Available at http://www.john-newling.com.2013/05/where-a-place-becomes-a-site-values-part-1-1995-013/ [Accessed 10 May 2014]

As we carried on developing our narratives and doing further research we discovered the story of Willoughby Spendlow, an old groundskeeper of the grandstand, and the story of a man who looked at the RFC mural while he waited to give blood. These were all incorporated into our narrative. There are examples of these narratives in any of our previous blog posts.

Improving aesthetics and atmosphere.

So far the performance was full of good content but was looking a little shabby so we talked about ways in which we could improve the aesthetics. We decided first that we would print off templates for all the paper airplanes so that the ending of the piece was effective but didn’t look so messy. We also made the decision to print labels to go on envelopes and type up and print all of the narratives. Although we thought that handwritten instructions seemed more personal we agreed that it was difficult to read and may affect the performance. We also decided to have a typewriter for Sam to type up her final narrative throughout the performance so it’s developed with the piece before it is delivered.

The final meeting and last minute changes.

The day before our tech rehearsal we made some quite drastic changes to the performance. Firstly we cut the performance in half to fifteen minutes as well as cutting our audience capacity practically in half; this meant restructuring the piece and prioritising which narratives and instructions we wanted to keep. The reason for doing this was so that the performance was more accessible to audience members. We knew that any of our participants would want to view different performances in the site and we didn’t want to put ourselves at a disadvantage by asking for too much of their time. We decided to only have one paper airplane in the performance rather than our original plan to have all audience members folding and throwing one at the end of the piece. This also meant that we had to change our idea for an installation piece at the end of the performance which I think was a great thing because we had no solid plans before, we had just agreed that we would develop something.

Installation: then and now.

Our original installation piece was based on having a number of paper airplanes and our research lead us to this image by Dawn Ng, from her work I fly like paper get high like planes:

Ng, D. (2009) ‘Dawn Ng’ [image online] Available at http://www.dawn-ng.come/new/paperplanes/4.html [Accessed 1 May 2014].

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qHRYiH8IqM8

(alicedalemusic, 2014)

Final Rehearsal.

This rehearsal was all about ensuring that our last minute changes had worked, we were fortunate to have a full audience to do a run of the performance and thankfully it all went well. We set up the space with fewer chairs than we had previously and it looked a lot more effective as well as making the performance more manageable:

All that was left to do after today was to print of labels for envelopes and correct a few spelling mistakes in the narratives we had printed off but other than that everything was ready to go.

Performance – Evaluation.

We had planned for four performances to begin at 2.15, 2.45, 3.15 and 3.45. We informed audiences via an information notice on the door which also contained background information on The Waiting Room in order to give it some context. We also informed audiences that the time capsule would be buried at 4.30. The room was set up for 2 o’clock and the difference is aesthetics from week one was huge:

Due to low audience members our first performance was cancelled but fortunately this meant that the 2.45 performance had seven audience members. This was by far our most successful performance; the audience responded well to the text and to the site and there were varying moments of awkwardness and discomfort that achieved exactly what we had aimed for. The most successful moment for me was when an audience member laughed for two minutes; it overlapped with a girl crying and a narrative about wedding vows and the moment wasincredibly surreal. The laugh didn’t belong in that moment and that is what made it so poignant

The second performance had only three audience members, therefore it was not as successful by far. One of the performers lost focus nd the audience did not respond so well to the text which may have been because they felt so isolated in the room. The third performance was much of the same though the group had fortunately managed to regain their focus. As the first performance had been cancelled we thought the third performance would be our final one but there had been miscommunications which lead to a full audience expecting a performance. As we had labelled all of our envelopes according to our planned performance times we managed to salvage a final performance by turning back all the clocks in the room and running the piece as though the time was 2.15. This performance ran well but still didn’t seem to evoke the same reaction as the first performance.

For me our entire process highlighted the dangers of relying so heavily on audience participation. In order to have improved the final performances I would have ensured that we always had a full audience, we could have combated this on the day by simply not performing until we had between six and eight audience members, but we didn’t feel like we shouldturn down audience members who did arrive. I would also ensure that all group members kept focus during the performances. I can admit that I lost focus slightly during our reset periods however it was very frustrating to see that the lack of focus from a performer effected the running of the piece.

Another change I would make would be to make more of the time capsule; I feel like it was such an important part of our piece that went slightly unnoticed by everybody whereas it could have been something that audience members were also a part of.

If I were doing the performance over again I would make a lot of changes, mainly because the way I interpret readings and works of other practitioners now is different to how I interpreted it at the start of this process. I feel as though The Waiting Room should have used a larger variation of works as inspiration becasue we seemed to decide on two performqnce influences and then let the site do the rest of the work. This being said, I am proud of our final performance. Of course there are things I would change however I think what we achieved was a success, certainly considering that four months ago I was being introduced to the concept of site-specific performance for the first time.

Works Cited

Alicedalemusic (2014) ‘The Waiting Room’ Time Capsule (Post Performance) [online video] Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qHRYiH8IqM8 [Accessed 10 May 2014].

Govan, E., Nicholson, H. and Normington, K. (2007) Making a Performance. London and New York: Routledge.

Ligna (2003) Exercise in lingering not according to the rules [online] Available at http://ligna.blogspot.co.uk/2009/12/radio-ballet.html [Accessed 10 May 2014].

Newling, J. (2009) Make a piano in Spain, 2008 – Wellcome Collection, London [online] Available at http://www.john-newling.com/2009/05/making-a-piano-in-spain-2008-wellcome-collection-london/ [Accessed 10 May 2014].

Pearson, M. (2010) Site-Specific Performance. London:Palgrave

Ng, D. (2009) Dawn Ng. [online] Available at http://www.dawn-ng.com/new/paperplanes/4.html [Accessed 1 May 2014].

Radiodispersion (2008) Radio Ballet Leipzig Main station Part 1 [online video] Available from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qI3pfa5QNZI [Accessed 10 May 2014].

RosieArches (2010) Rotozaza’s Etiquette // Part of the Arches OFF-SITE // 9-13 Feb 2010 [online video] Available from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-iU7mzaktsQ [Accessed 10 May 2014].

Rotozaza (2007) Etiquette. [online] Available from http://www.rotozaza.co.uk/etiquette2.html [Accessed 10 May 2014].

![Metro-Boulot-Dodo’s Blownup takes place under the red wash of the developer’s light, a familiar representation of the darkroom. Metro-Boulot-Dodo [Production still from Blownup] n.d. [image online] Available at: http://farm6.static.flickr.com/5207/5222937999_2e0db20c78.jpg. [Accessed 22 March 2014].](https://sitespecific2014mpi.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2014/03/metro-site.jpg)

Drop off point.

Drop off point.