‘It’s not just about a place, but the people who normally inhabit and use that place. For it wouldn’t exist without them’ (Pearson, 2010, 8)

During the Second World War the Lincoln grand stand was set to be used as a mortuary. It is currently being used as a playgroup centre for toddlers- an interesting juxtaposition to its potential former purpose. This contrast between new life and death influenced my group to research into the children who would have been taken to the mortuary during World War 2, however with very different intentions than today.

In our work we used the information we found at Lincoln’s Archives, as ‘A large part of the work has to do with researching a place, often an unusual one that is imbued with history or permitted with atmosphere’ (Pearson, 2010, 7). We found information on a young girl named Margret, who was from Lincoln and unfortunately died in a explosion during the Second World War, so we initially used her story to base our performance on, however, during our research process I found that two more children also died in the same event, Anthony and Lawrence Thacker. All three children of Highfield Avenue, Lincoln were in their houses when the explosion went off and sadly they all lost their lives, therefore all three bodies would have been preserved at the mortuary. As Carley writes when speaking about Rachel Whitereads Ghost, ‘To be haunted is to bring past impressions to bear on current circumstances, interpreting new phenomena in light of them’ (2008, 27). A modern day nursery is happy place- active children, a place to socialise and a room where futures begin. To think that this room was once a mortuary is haunting in itself. With this in mind we decided to place the story of the three children’s premature death within this happy environment, creating links between the cupboard that stores the children’s toys in today and the corpse outline we would create on the floor to portray the vast journey and transformation of this single room within the past 60’s years.

Our performance took place at Lincoln’s Grandstand main room on the 8th May 2014 from 2pm-5pm. The audience were invited to the ‘Mortuary room’ to watch a video showing us recreate the journey from the houses of the three children on Highfield avenue, to their gravestones and finally to the grandstand’s mortuary room where the performance took place. The audience were also able to view the taping of the bodies and pay their respects for the three children whilst listening to an audio recording describing what happened in the accident.

Our overall intention was for our audience to see the grandstand in a different light to how they may see it today. Pearson states that performance can ‘illuminate places that do not so easily reveal themselves but which have their own unique characteristics, qualities and attractions’ (2011), therefore we wanted to show this unique characteristic the grandstand once had in our performance.

If we were to visit a site on a one off occasion or pass by in a car we would think subjectively about it for example, what colour the building is or what material it’s made out of ect. As Lincoln’s grandstand was a site we would start visiting weekly it would become personal to us, therefore we decided look deeper into the historical content of the building as, ‘Layers of the site are revealed through reference to: historical documentation’ (Pearson, 2010, 8). We began to search the space and for clues, in one room there was Latin language painted on the wall, these words translated to ‘through struggles to the stars’, as we researched into this we found that it was written in memory of the RAF members who died in the war, this showed us an example of Macaulay’s idea that, ‘The site may begin to tell its own story’ (Pearson, 2010, 9) . This small piece of information led us to do more research into the grandstand during the war time, this was the moment we found that it was set to be used as a mortuary- our first and most important piece of information that would begin our Journey towards our performance.

Willi Dorners ‘packed bodies in urban spaces’ inspired us to begin to measure the space with our bodies. Dormer’s performers used their bodies to fill a small space in public areas creating juxtapositions that would stand out. Physically using our bodies gave us a better understanding of how the mortuary may have looked for example laying our bodies in the small kitchen area created an overflowing atmosphere- this is how we imagined the mortuary to look with all the dead bodies. We then took Dorner’s idea to, ‘Build a space- with chairs and tables plot journeys through the space and then move the chairs and tables and try to make the same journeys’ (2005). This influenced the way we walked as we had to slow down and concentrate on our balance in order to dodge chairs and obstacles. We then realised that people would’ve walked around the mortuary in the same way- out of respect, whereas today the room is full of fast movement and pace when the children go for their play group sessions, therefore Dorner’s guidance helped us find a juxtaposition between the grandstand during the war time and the grandstand today, ‘Play around with ideas. Very important- when you lose playfulness you lose inspiration. Stay playful. Set tasks. Find juxtapositions’ (Dorner, 2005). This then inspired us to somehow incorporate the children of today into our performance, as they show a huge juxtaposition between the atmosphere at the grandstand now and the atmosphere at the grandstand during the war. Rachel Whiteread’s first solo exhibition ‘ghost’ was also an inspiration for our performance because she brought history from war time to create her performance, ‘The exhibition consisted of a collection of plaster casts derived from pieces of post war furniture’(Carley, 2008, 26). She took pieces of history and brought them to a modern day setting, ‘Ghost foregrounds the inward-looking, opaque qualities of Victorian domestic spaces, in contrast to Modernist space conceptions of the interior’ (Carley, 2008, 26) therefore this juxtaposition between past and present would’ve also been the main focus of her performance.

As the mortuary was going to be the main focus of our site-specific performance, we decided to visit Lincoln Archives to try and find any information that could inspire us as, ‘both archaeology and performance involve the documentation of practices and experiences’ (Pearson, 2001, 55). At the archives we found information on a young girl named Mary Elaine Marriott who passed away on the 11th June 1943 in her home whilst doing her homework. Her death was caused by a bombing plane, its wing tipped onto a telegraph pole; this caused an explosion and hit 3 houses on the street including hers. The next day when we visited the grandstand we all wrote response letters from what we had found at the archives, when everyone read their letters out at the same time it made me think of prayers being read and therefore urged me to want to do a performance in memory of Margaret. Racheal Whitereads Ghosts, was described as ‘carefully and deliberately conjured from the ether blanketing the interior limits of the room, manifesting an afterlife for an abandoned piece of architecture.’ (Carley, 2008, 26). This interested me as is shows you can recreate a memory through symbolism, this gave me the idea of taping a body on the floor to representing Margaret’ presence in the room when it was used as a mortuary. The marked out body made me think of a crime scene, we then added post-stick notes to the body labelling possible injuries Margaret may have had. We hoped that the taped bodies would ‘illuminate the historically and culturally diverse ways in which a particular landscape has been made, used, reused and interpreted; and help us make sense of the multiplicity that resonate from it’ (Pearson, 2011).

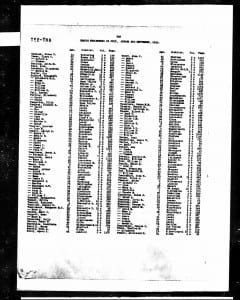

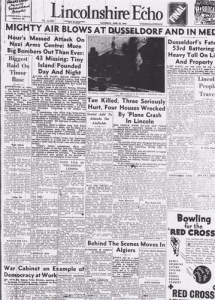

Using a family tree software I was able to find out who else was injured in the event and what injuries they suffered from, ‘performance can enable integrations of academic research’ (Pearson, 2011). I found an article from the Lincolnshire echo that was written one day after the event (12th June 1943):

‘Ten people were killed and 3 seriously injured when a plane crashed on houses in Highfield Avenue, Lincoln, early last night. 8 people – 5 members of the crew of the plane and 3 civilians were killed instantly and another member of the air crew and a child died later in hospital. Civilians killed were Margaret Marriot age 11 of 25 Highfield Avenue, Mrs. J. Thacker of 24 Highfield Ave and Miss Gwendoline Whitby age 42 of Hykeham Road, Lincoln. Laurie Thacker aged 4 who was admitted to hospital with burns died during the night. The 3 injured who are detained in hospital are Harry Bishop of Highfield Ave., his wife Mrs. Esme Bishop and Anthony Thacker aged 3 also of Highfield Ave.’ (Unknown, 1943).

After finding this information we began using our time at the grandstand to tape around each other’s bodies to represent the ten that had died, hoping to show that, ‘location can work as a potent mnemonic trigger, helping to evoke specific past times related to the place and time of the performance and facilitating a negotiation between the meaning of those times’ (Pearson, 2010, 9). The picture below shows our first attempt of taping a body,

This took 5 minutes to complete, as you can see it didn’t look very realistic, we realised that in order to create realistic outlines of all the bodies it would be time consuming, and because the grandstand was only open for three hours on our performance day it was a sensible idea to tape less bodies, we wanted to do Margaret’s as she was our initial stimuli, we also wanted to do Laurence’s body as he was another child that died. Focusing on the children affected by this incident would make more sense as we wanted to show the juxtaposition with the toy cupboard. Whiteread’s Ghosts, ‘bears the impressions of the specific room from which it was cast, but it is also laden with the impressions of past rooms brought to bear on it by viewers.’ (Carley, 2008, 27). This shows how past life can be brought to new surroundings and still fit in, just like the children that died would fit in at the grandstand now as it’s a place for children. With this in mind i went to do some more research to find if Anthony Thacker (the boy who was taken to hospital) had died or not in this incident.

Searching through documents of deaths i found Margaret’s and Laurence’s documented death both in June. Antony died in September after suffering with extremely bad burns in hospital. As there were three people in our group we decided to focus on the three children that died and have an outline of each of our bodies, representing the three deaths.

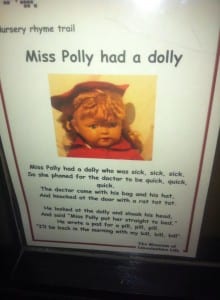

The group then visited the Lincoln Life Museum in hope of finding any more information that could influence our performance, I found a song that young children would’ve sang during the war time called ‘Miss Polly Had A Dolly’ The song had lyrics such as ‘she called for the doctor to be quick’. As the song was time relevant to when the children were alive and fit well with the mortuary and the children’s play centre theme I decided that we should incorporate it into our performance as ‘both archaeology and performance involve the documentation of practices and experiences’ (Pearson, 2001, 55).

Michael Pinchbeck’s performance, The Long and winding road shows Michael on a journey where he filled a car with his brothers memories and drove them to the scene of his death, Michael explained,

‘The car was packed with 365 mementoes wrapped in brown paper and string, tagged and logged. The journey lasts until 17 May 2009 when I will drive the car into the River Mersey. The journey started with a letter to my brother. The letter became a parcel. The parcel became a suitcase. The suitcase became a car. This is my car. This is my car history. This is the end of the road. (Pinchbeck, 2009)

This inspired myself and my group into recreating the three children’s journey, where we would also finish the journey at the end of the children’s road- the mortuary. We decided to start the journey at the houses where the children lived, number 25 for Margaret and number 27 for the Thacker brothers as this was where we expected these children to have held most of their memories.

Next we walked to the children’s gravestones. This for me was the first time I felt a emotional connection with our piece as it finally felt real and I knew these facts I had researched were all correct, ‘a shift in form can be noted from performance that inhabits a place to performance that moves through spaces’ (Pearson, 2010, 8) As we walked to the graves we passed a field with a park, it made me wonder whether these children would have played on this field like the children now play at the grandstand, ‘moving between places, wayfinding, more closely resembles story-telling than map using. As ones situates ones position within the context of journeys previously made’ (Pearson, 2010,15).

And finally we then walked up to the grandstand, where the children would have been taken after their deaths. As we wouldn’t be able to have our audience with us on our 3 hour journey we had to show the footage on the day of the performance, this explains the reason we made the journey to the grandstand our last so that the the audience would get the sense that we had just finished the walk and at that moment we were bringing the memories of these children to life once again at the grandstand. Haunting can be both extramundane and mundane; it can be mobile or site specific. To haunt is to be insistently and disturbingly present,particularly in someone’s mind.’ (Carley, 2008, 27)

Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s Her Long Black Hair also shows a journey. This journey retraces the footsteps of woman. Cardiff describes this performance as, ‘one foot in the past and one foot in the future” (Derkson, 2012, 4). Therefore I took an interest in her work as we wanted to show the same juxtaposition. In this performance audio was used, therefore audience members were able to hear memories of this woman and also see pictures. On our journey we were not going to have the audience with us which meant they may not understand what actually happened to these bodies we were going to be taping or who’s bodies they were. Therefore we decided to add audio into our performance so that the audience knew the real facts. I researched and found quotes from the Eco on the event such as;

‘Mr. W. H. Chester of 20 Highfield Ave. gave a vivid account of the crash. “We heard a roar of engines”, he said. I remrked to my wife “Surely this is going to crash” and we dashed to the back door’

“The plane was just coming over the house tops behind Highfield Ave”. As I got to the doorway it seemed to be heading straight for our house, but he dipped one wing and banked away. The same wing then struck a telegraph pole and snapped it off.’

‘The impact toppled the plane over so that it crashed into the houses on the opposite side of the road and finished facing the direction it had come. As it struck the houses there was a blast of explosive petrol and oil was thrown over’ (unknown,1943)

We decided to write these quotes incorporated with descriptions of the children such as age, birth date, death date, address ect and read them out in the style of a news report this would create a sense of seriousness while we were taping the bodies, this reflects De Heddon’s idea of juxtaposing the ‘the factual with the fictional, event with imagination, history with story, narrative with fragment, past and present’ (Pearson, 2010, 9)

As we used the main room, audience members were constantly passing through and therefore could see the process of our performance, firstly the video of our journey during the first hour and secondly the taping and covering of the bodies whilst listening to the audio. We had cards and flowers laid out on the floor next to where we were taping the bodies during our performance; this explained briefly information on the event and the three children. As these cards were laid on the floor audience members had to kneel down to read them, this looked like they were praying for these children and was an effective example of Rom’s opinion that, ‘it was frequently not the locations that invested the performances with a sense of identity, as Harvie proposes, but the performances that made these locations and histories associated with them representative of such an identity’ (Pearson, 2011,9). Therefore the audience were involved in the performance without even realising.

When I noticed the audience members kneeling down I thought it would’ve been interesting if we had a whole bucket of flowers rather than just the three that represented the children, this way the audience could’ve laid a flower in respect to the children, however even without this act in our performance I believe the audience showed enough respect, we were in the main room and therefore it was quite noisy however on our half of the room audience members tended to quieten down. As the audience gave this type of reaction, I believe that we showed the representation of the children well, Like in Whiteread’s Ghosts ‘the viewer observes the cast of the room from the perspective of the room itself. A ghost usually returns to haunt the terrestrial scene of its death’ (Carley,2008, 28) I believe that we showed the presence of Margaret, Laurence and Anthony in the building which was challenging to do so as looking at the grandstand today its extremely hard to tell that it was set to be a mortuary. The video also worked well as ‘receiving landscape is this ‘to carry out an act of remembrance’ (Pearson, 2010, 16)’ which is what our main focus was.

Our final performance should have used the to cupboard that is used today however on the day we were not able to access it, therefore we improvised with a projected image of child onto the toy cupboard door to show the connection. I believe that if we were able to have access to the cupboard (as we had been told we would) then our performance would have been improved as it would have given solid proof to audience members that the room is now used a playgroup and therefore would have shown the juxtaposition more clearly.

When I first saw the grandstand i thought the only type of performance we could’ve created would have been horse-related, what I did not understand is that ‘within contemporary performance, site related work has become an established practice where an artists intervention offers spectators new perspectives upon a particular site or set of sites’ (Govan et al, 2007, 121) therefore through my own journey I have realised that sites are not always what they seem to be and there is always a historical story behind it.

Works cited

Carley, R. (2008) Domestic Afterlives- Rachel Whitereads Ghost. Architectural Design.78 (3) 26-29.

Derkson, C. (2012) Walking the edge of the stage in theory; or, Janet Cardiff’s sensorium for intermedial . Theatre research in Canada, 33 (1) 1-23.

Dorner, W. (2005) In: Pinchbeck, M. (2014) ‘Site Specific Peformance, Week 2: Practice’. Lecture, Seminar Room MB1008, Lincoln: University of Lincoln. 6 February.

Govan, E. Nicholson, H. and Normington, k. (2007) Making a Performance- Devising Histories and Contemporary practices. Oxon: Routledge.

Pearson, M (2010) Site specific performance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pearson, M. Shanks, M. (2001) Theatre/Archaeology. Clondon; Routledge.

Pearson, M. (2011) 1) Why Performance? [online] Nottingham: Landscape and Environment programme. Available from, http://www.landscape.ac.uk/landscape/documents/eventpapers/toolkit/1whyperformance.pdf [Accessed 16th May 2014].

Pinchbeck, M. (2009) The Long And Winding Road- An online account of a 5 year live art project from 2004-2009. [online] Available from: http://www.acarhistory.blogspot.co.uk/2009/05/final-words.html [Accessed 16th May 2014]

Unknown. (1943) TEN KILLED, THREE SERIOUSLY HURT, 4 HOUSES WRECKED BY PLANE CRASH IN LINCOLN. Lincolnshire echo, 12 June.